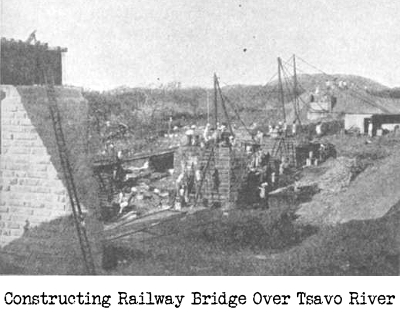

Fatal animal attacks on humans are not unusual. What is unusual is when an animal displays such an awareness and intelligence that the hunter becomes the hunted. This was the case when two lions methodically stalked and devoured over a hundred construction workers building a railway bridge over the Tsavo River in Kenya during a period of nine months in the late 19th century.

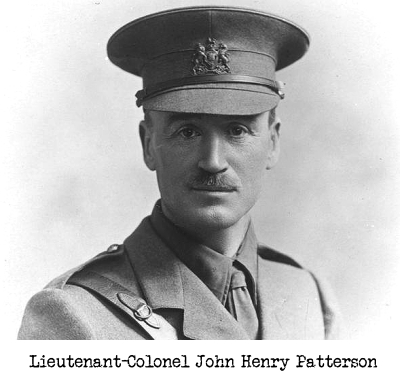

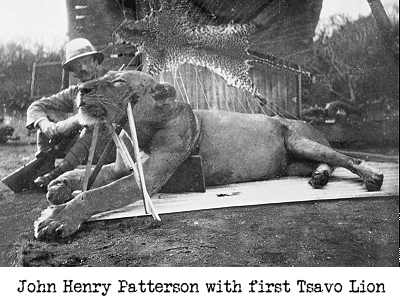

In March 1898, the British began building a bridge over the Tsavo River as part of a railway linking Uganda with the Indian Ocean at Kilindini Harbor. The construction site consisted of multiple camps spread out over an area of eight miles to accommodate approximately 3,000 Indian and African workers. The project was overseen by Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson who, coincidentally, was an experienced tiger hunter from his military days in India.

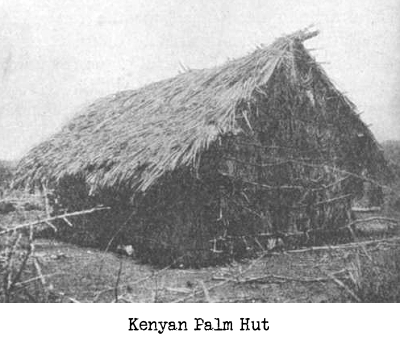

Just a few days after his arrival, Patterson received word of missing workers. He brushed aside the news including a fantastic rumor that a pair of maneless male lions were stalking the campsites at night and dragging people from their palm huts and cloth tents. Bandits were active in the area and Patterson assumed they were the source of the problem.

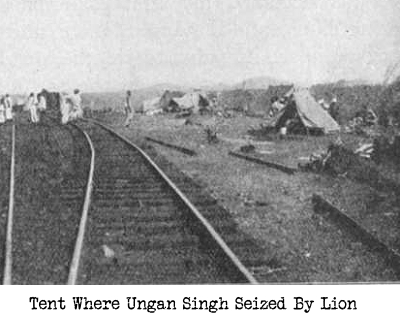

Three weeks later, a Sikh Jemader (supervisor) named Ungan Singh was seized from inside his tent by a lion in front of horrified workers. The following morning, Patterson went to the scene and came across several pools of blood. When he stumbled across Singh’s corpse, nothing remained except scraps of flesh, several bones and the largely intact head of Ungan Singh who died with such a terrified grimace on his face that it traumatized Patterson.

John Henry Patterson suddenly realized he had a huge lion problem on his hands.

But this was Africa, lions had attacked humans since antiquity and the locals had traditional methods to deal with them. Lions prefer to hunt in total darkness, so the railroad employees kept huge bonfires burning throughout the night and built impassable whistling thorn fences (bomas) encompassing the camps. They also enforced a curfew – not that anyone wanted to be walking alone after dark.

It was all to no avail. The light from the fires did not deter them and the lions either leapt over or crawled through the thorn fences. These creatures weren’t behaving like ordinary lions and many of the superstitious workers believed they were revengeful spirits angry about the construction of a railroad through their ancestral land. They named them The Ghost and The Darkness.

The killings continued unabated through March and then – they stopped.

No one knows why the lions left, but Patterson must’ve breathed a huge sigh of relief. Word spread quickly throughout the camps that the lions were gone. Workers who had threatened to flee went back to constructing the railway bridge. For two months everything ran smoothly.

In June, Patterson received a report about a missing worker. Fearing the worst, he soon received another report, and then another and another. The lions were back in force and they began snatching and devouring sleeping workers at the rate of one a day. Those who survived these attacks could actually hear the lions crunching on the bones of their comrades somewhere outside their camp.

The British sent 20 Sepoys (Indian infantryman) to hunt the lions. They set numerous traps with poisoned animal carcasses and hid in the trees with their guns trained on anything that moved. Nothing worked. The lions simply ignored the carcasses and circumvented the soldiers to get inside the camps. They even attacked the hospital, killing one patient and severely mauling two others.

The pace worsened. In the beginning, the two lions would snatch one worker and carry him screaming off into the bush. Now, the lions were each grabbing a worker.

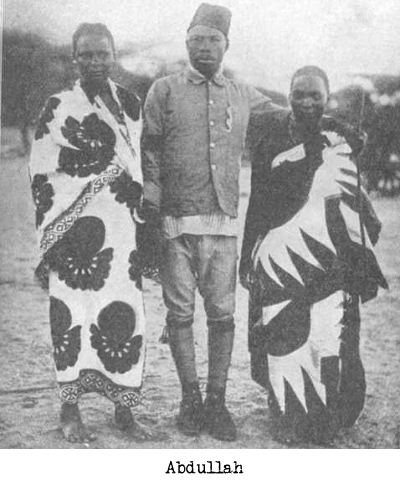

Patterson requested Askaris (Native soldiers). The District Officer, a Mr. Whitehead, arrived at the train station with Abdullah, an Askari sergeant, to appraise the situation. Unfortunately, their train arrived after nightfall. As they walked to the camp with their lantern, Whitehead was ambushed and knocked to the ground by one of the lions. He managed to fire his gun in the air and escaped with four claw marks deeply gouged down his back, but Abdullah was snatched and devoured.

Patterson wrote, “I have never experienced anything more nerve-shaking than to hear the deep roars of these dreadful monsters growing gradually nearer and nearer, and to know that someone or other of us was doomed before dawn.”

“Lion Hunter” was not in John Henry Patterson’s original job description, but after months of failure and mounting casualties he’d had enough. From his experience as a tiger hunter in India, he realized the task would be especially dangerous. He would be hunting these lions alone and they were working as an effective and deadly pair. Patterson had the firepower to kill them, but his advantage ended there.

On December 1st, workers began boarding any train heading for the coast, 130 miles away. Those who stayed were too frightened to sleep in their huts and tents. So many slept on the limbs of a large tree that it came crashing to the ground. Work on the railway bridge came to a halt. The lions were winning.

To make matters worse, the tactics Patterson employed hunting tigers in India proved totally ineffective in the African bush. The lions seemed to outsmart him at every turn. Workers were dying and the success or failure of the railway bridge project rested solely on his shoulders. He needed a lucky break.

On December 9th, a breathless worker excitedly informed Patterson that one of the lions had attacked a man and his donkeys down by the river. The man had escaped and the lion was now busy feasting on one of the animals. Seizing the opportunity, Patterson grabbed a double rifle and bolted down to the river. He crept unnoticed to within 15 yards of the beast, aimed for its skull, held his breath and gently squeezed the trigger.

Click.

The gun misfired and the lion glared at Patterson through primal amber-colored eyes. Patterson was so terrified that he forgot to pull the trigger on his second barrel. The beast could’ve pounced in a flash and torn him to shreds. Instead, he turned his maneless head and trotted off.

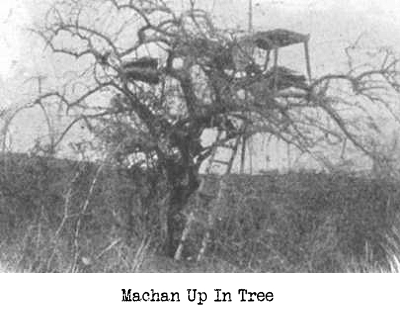

Relieved to have escaped certain death, Patterson noticed that the donkey had only been partially eaten and there was an excellent chance the lion would return. He quickly built a machan (blind) twelve feet up a tree almost directly above the carcass.

It was nightfall when Patterson began his solitary watch. He waited and waited until his eyelids grew heavy and he fell asleep. A noise from the bushes awakened him. The lion had returned and slowly began to encircle him, drawing nearer and nearer. The hunter had now become the hunted.

Patterson could hear the lion, but not see him. The crunching sound of underbrush steadily became louder until it stopped. He slowly peered down to see a massive lion staring straight up at him. Before it could scale the tree, Patterson fired his gun and kept firing.

The lion thrashed in agony before darting into the bush. His gunshots were heard in the camp and a torch-bearing crowd soon appeared. After yelling that he was unharmed, he instructed the workers to go no further and follow him back to camp. There is nothing more dangerous than a wounded animal and, while Patterson believed his shots had been fatal, he wasn’t about to find out in the dark.

At daybreak, he followed a short blood trail and found the lion. It died after one of his bullets had pierced the animal’s heart. Another bullet had struck its hind leg. Patterson had emptied his chamber pointing straight down from only twelve feet away and was shocked to learn he had hit the lion only twice, and only one shot was fatal.

The lion was nine feet, eight inches long. It took eight men to carry the carcass back to camp.

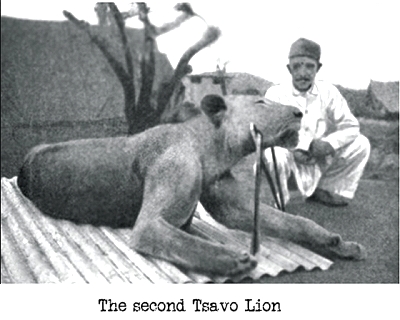

One down, one to go, but the second lion was the stuff of legend.

Patterson received word that the other lion had killed and eaten two goats on a camp inspector’s veranda. He tied three live goats to a 250-pound length of steel rail to anchor the animals on the veranda and then built a machan in a tree above the bait. The lion returned that evening and killed one of the goats before proceeding to drag all three goats and the heavy steel rail into the bush. Patterson managed to get off a shot, but hit one of the goats.

The next morning he tracked the animal accompanied by his gun-bearer, Mahina, and a search party. Killing the first lion unnerved him and he was no longer going alone. After only a quarter-mile, they heard a terrific roar and the lion charged out of the bush, sending men scrambling in all directions. Instead of pursuing anyone, the lion scampered away. Patterson constructed a machan up a nearby tree and sat beside Mahina who was guarding an armful of rifles as the sun set below the horizon.

Patterson was beginning to doze off when Mahina gently squeezed his arm. He looked down to see the silhouette of a large lion lurking below them. Patterson quickly took aim and simultaneously fired two powerful blasts into the shoulder of the animal. The lion fell to the ground and remained still. He had no doubt they were both fatal shots. Patterson was ecstatic.

And then, the lion shook it off and ran into the bush.

Patterson was flabbergasted. He’d never seen an animal react like that to such devastating firepower at close range. The next morning, he and his search party followed its blood trail for over a mile until the dusty crimson droplets stopped with no lion in sight.

For ten days there was no sign of the lion and Patterson began to believe that the animal had wandered off to succumb to its wounds.

On December 27th, Patterson was alerted to the lion’s return by the sound of gunfire chasing it away from underneath a large tree filled with screaming Indians. Paw prints showed that it had breached the camp perimeter and actually poked its head inside some of the empty huts.

Patterson was more determined than ever to kill the beast. He constructed a machan in a nearby tree and sat armed to the teeth with Mahina, each taking turns on watch.

At approximately 3 am, Mahina was on watch when Patterson opened his eyes. His instincts sensed something wrong. Looking down, he saw the lion emerge and realized it had been stalking them all along. Patterson aimed his rifle and shot a .303 bullet into the lion’s chest. It showed no reaction and disappeared.

The following morning, Patterson spotted the lion camouflaged in thick bush. His first shot flushed the animal and it charged him. His second shot knocked the lion off its feet, but it rebounded and kept coming. He fired a third shot that hit the animal with no effect.

Patterson reached for his back-up Martini rifle and, to his horror, realized he’d forgotten it. Running for dear life with the lion in hot pursuit, Patterson managed to scramble up to the machan just as the lion reached the base of the tree. Grabbing a fresh rifle from Mahina, he fired down at the lion and it dropped to the ground.

The lion remained motionless, but Patterson waited until he felt it was safe to descend the tree. He had no sooner stepped on the ground when the lion roared back to life. In utter disbelief, Patterson frantically pumped bullets into the lion’s chest and head, finally stopping the beast only a mere five steps away from where he was standing. Patterson said the lion took its last dying breath reaching out to touch him with a massive claw.

Though he proved much harder to kill, the second lion was slightly shorter in length than the first, measuring nine feet, six inches.

Patterson claimed that 135 people had been killed and devoured building the railway bridge over the Tsavo River. The railway documented 28 Indian deaths. The Field Museum in Chicago, where the lions are displayed today, believes there were a total of 35 victims. Patterson blamed the large discrepancy on the fact that most of the killings were in the African camps and none of those were documented.

Completed in February 1899 at an enormous cost in human blood and suffering, the railway bridge over the Tsavo River was destroyed less than twenty years later by the Germans in World War One.

David J Castello