Columbus never stepped foot on American soil in 1492 or during any of his three successive voyages. It was Juan Ponce de León, who accompanied Columbus on his second voyage in 1493, who finally did so on April 3, 1513, somewhere just north of present-day Saint Augustine, Florida.

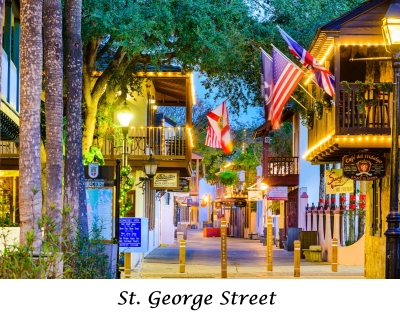

Founded on September 8, 1565, by Spanish Admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, Saint Augustine is truly a magical place. Home to the imposing fort Castillo de San Marcos (1695), it is the oldest continuously occupied city in the United States. The city also includes Flagler College, ranked #2 in US News & World Report’s list of Best Regional Colleges in the South, and, on St. George Street, the oldest wooden school house in the nation is still held together by chains.

On any given day, Saint Augustine’s narrow red brick streets and multi-colored Spanish colonial-style buildings are packed with tourists and students savoring its many pubs and restaurants, and touring the Castillo de San Marcos. Looking west from the Intracoastal Waterway down Cathedral Place, one would think they were in Europe.

But those happy faces visiting Saint Augustine mask a terrible truth. The birth of Saint Augustine, its very foundation, was baptized in blood in the sixteenth century.

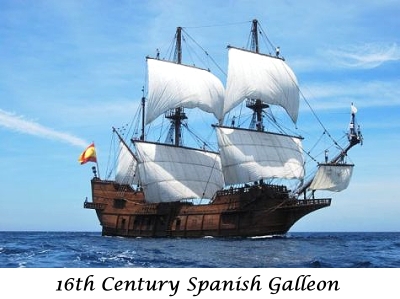

Today, Florida is the southernmost part of the United States bordering the Atlantic Ocean. In the sixteenth century, it was the northernmost leg of a massive Spanish empire that stretched over 4,000 miles down through South America. Laden with gold and silver, fleets of Spanish galleons would sail north before catching the Gulf Stream current along the coast of Florida and heading east to Spain.

Spain built a series of forts along the nautical route to protect their precious cargo. It was vital that they established a fort as far north as possible. The French were already casting a covetous eye on land in north Florida and the Spanish treasure fleet would be vulnerable to attack just before they steered back to Europe.

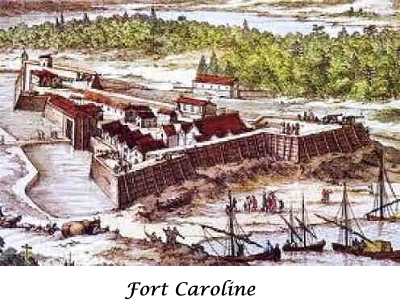

In early 1564, Menéndez, now Captain General of the Fleet of the Indies, asked Spain’s King Phillip ll to fund a fleet to sail to Florida to search for his son, Admiral Juan Menéndez, who had been lost in a hurricane in the area in 1563. His request to find his son went unanswered, but in 1565 the King was angered to learn that the French had built an outpost, Fort Caroline, at present-day Jacksonville. He ordered it destroyed and assigned the mission to Menéndez.

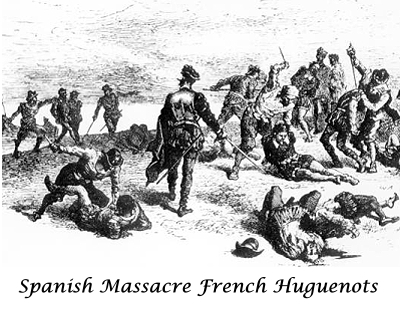

King Phillip ll not only wanted Fort Caroline annihilated, he wanted its French Protestant Huguenot soldiers executed, whom the Roman Catholic Spanish considered heretics. Unlike other parts of Europe, there were virtually no Protestants in 16th century Spain and they were treated harshly. This was the era of the Spanish Inquisition and the penalty for heresy for unrepentant men was to be burned alive at the stake. If you repented, you were afforded the quicker death of being garroted (strangled) first, then burned.

King Phillip ll was sending Pedro Menéndez de Avilés on a mission of death and destruction.

On the feast day of Saint Augustine of Hippo, August 28, 1565, Menéndez and his fleet, comprised of his 600-ton flagship San Pelayo and several smaller ships carrying over 1,000 sailors, soldiers, and settlers, sighted land off the north inlet of the tidal channel that the French called the River of Dolphins.

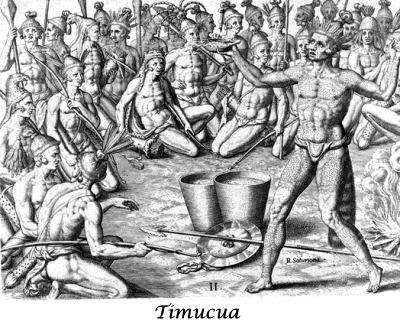

Menéndez slowly sailed north on September 4th, carefully investigating every inlet and smoke trail trying to find the French while not disturbing the local Native Americans. The area was inhabited by the powerful pre-Columbian Timucua and the last thing he needed was a conflict that might give away his position.

Thirty miles north he sighted four ships at the mouth of the Saint Johns River belonging to the French Explorer Jean Ribault. Fort Caroline was six miles upriver. After a brief skirmish, the French ships cut their anchor lines and fled with Menéndez in pursuit. Unable to catch the faster French vessels, he abandoned the chase and sailed back to the River of Dolphins, dropping anchor on September 6th. Menéndez and his men hastily began constructing a fortification of palm-log and earthworks around an existing Timucuan village. Completed two days later, he named the settlement, Saint Augustine.

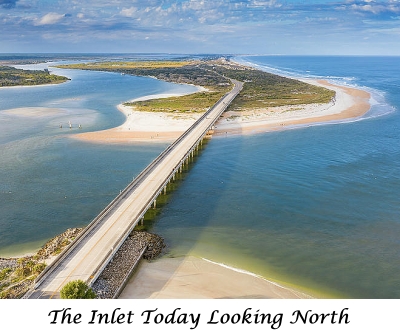

The San Pelayo was too large to cross the sandbar into the Saint Augustine Inlet and on September 10th Menéndez ordered it to sail to Hispaniola with another ship, the San Salvador. Hours later, Jean Ribault appeared with his four ships and nearly captured Menéndez who barely managed to escape by crossing the sandbar in a small sloop. The French ships were too large to enter the inlet, so they sped south to pursue the San Pelayo and San Salvador.

Before they could overtake the Spanish ships, Ribault and his fleet collided with a violent storm, most likely a hurricane. September is the height of hurricane season and three of Ribault’s ships wrecked seventy-five miles south of Saint Augustine at present-day Ponce de León Inlet where most of the men drowned and some fifty were captured by the Timucua. Ribault’s flagship La Trinité beached a further sixty miles south near present-day Cape Canaveral.

Correctly assuming that Fort Caroline was weakly defended, Menéndez marched with 500 men overland during the storm and launched a surprise attack on September 20th slaughtering all 132 of the remaining Frenchmen, but sparing sixty women and children. He left a garrison behind and renamed the fort, San Mateo.

The surviving French at Ponce de León Inlet, estimated to be 140 out of an original 400, began the arduous trek north along the beach not knowing there was no longer a Fort Caroline. Meanwhile, the Timucua had raced ahead to inform the Spanish. On September 28th, Menéndez, accompanied by sixty soldiers, some officers and a Roman Catholic priest, saw the French soldiers’ campfires across an inlet they were unable to cross fifteen miles south of Saint Augustine.

The French soldiers were exhausted from surviving the storm, harassment by the Timucua and their sixty mile march up the beach. The next morning, one Frenchman swam safely across the inlet and threw himself at Menéndez’ feet pleading that they hadn’t eaten bread for over a week and imploring him to allow the French to continue unharmed to Fort Caroline as they were not at war with Spain.

Menéndez wrote King Phillip ll, “I answered him that we had taken their fort and killed all the people in it because they had built it there without Your Majesty’s permission, and were disseminating the Lutheran religion in these, Your Majesty’s provinces. And that I, as Captain-General of these provinces, was waging a war of fire and blood against all who came to settle these parts and plant in them their evil Lutheran sect; for I was come at Your Majesty’s command to plant the Gospel in these parts to enlighten the natives in those things which the Holy Mother Church of Rome teaches and believes, for the salvation of their souls. For this reason I would not grant them a safe passage, but would sooner follow them by sea and land until I had taken their lives.”

The Frenchman returned to his comrades with the dire news. No mercy from Menéndez was promised and he refused a ransom offer of 5,000 gold ducats. There was no longer a Fort Caroline. They could only hope for the best. If they stayed at their position, they would either starve to death or be picked off to be tortured by the Timucua. The decision was made to surrender.

After disarming and sending their weapons across the inlet, they were rowed by the Spanish across in groups of ten. To not arouse suspicion, they were well treated as they crossed. Once landed, they were given food and drink to strengthen them for the journey. Then, their hands were tied behind their backs and they were marched over the sand dunes, out of sight, in the direction of Saint Augustine.

At the distance of a gunshot, Menéndez had drawn a line in the sand with his spear. Upon reaching this point, the stunned prisoners were forced to kneel and were beheaded by knife. They were too far away for their screams to be heard. This parade of execution continued into the night as each group of ten men was marched silently to their death until 130 soldiers had been massacred. Ten were spared by the intercession of the Spanish priest after discovering they were Roman Catholic.

On October 10th, Menéndez received word in Saint Augustine that Jean Ribault and 150 French survivors from his flagship La Trinité were camped south of the same inlet as the first French group. They, too, could go no further. The Timucua told the Spaniards that the French were starving and would offer little resistance. Menéndez departed with 150 of his men and arrived that evening.

At sunrise, Jean Ribault spotted the Spanish across the inlet. He immediately displayed his banners, sounded his fifes and drums, and offered battle. Menéndez and his men simply ignored them. Realizing the futility of his situation, Ribault raised a white flag.

A French Sergeant Major was ferried across to discuss terms of surrender. Menéndez told him there were none and led him across the sand dunes to show him the corpses of the French who had been killed twelve days earlier. Why he did this has never been explained. Regardless, he informed the Sergeant Major that no harm would come to Jean Ribault if he wanted to speak.

Ribault accepted his invitation and was graciously offered wine and preserves by his host. However, he had no appetite after learning of the massacre of his French comrades. He tried to sway Menéndez with 100,000 gold ducats, an incredible sum of money at the time, but was refused.

Jean Ribault informed his men of their predicament. Mercy was not to be expected, but there was always hope. The majority of the men, eighty, adamantly refused to cross and disappeared into the wild. History does not record their fate. The remaining seventy French gambled their lives and were ferried across the inlet in groups of ten. Seventeen of them, the drummers, fifers, trumpeters, and four others, were deemed Roman Catholic and pardoned. The remaining fifty-three, including Jean Ribault, were promptly executed.

Menéndez wrote King Phillip ll, “I put Jean Ribault and all the rest of them to the knife judging it to be necessary to the service of the Lord Our God, and of Your Majesty. And I think it a very great fortune that this man be dead; for the King of France could accomplish more with him and fifty thousand ducats, than with other men and five hundred thousand ducats; and he could do more in one year, than another in ten; for he was the most experienced sailor and corsair known, very skillful in this navigation of the Indies and of the Florida Coast.”

Today, that inlet, a small fort and the adjoining river whose source is Saint Augustine are known as the Matanzas Inlet, Fort Matanzas and the Matanzas River.

Matanzas is the Spanish word for slaughters.

David J Castello