No one will ever know the true wind speed, barometric pressure or death toll of the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane, the most powerful Atlantic storm to make landfall on the United States.

The official numbers are sustained winds of 185 mph, barometric pressure of 892 mb and 485 fatalities. The problem with those statistics is that there is plenty of evidence to refute each. In fact, the reality was worse.

In 1935, there was no radar to track hurricanes as they came barreling in from the Atlantic or Gulf of Mexico. Weathermen relied on ship-to-shore reports. Even though there were plenty of ships at any given time, the information they provided gave meteorologists, at best, a general idea of the storm’s location. These reports could be highly inaccurate, especially if a hurricane suddenly intensified from a Category 1 to a Category 5 monster.

Which is exactly what happened.

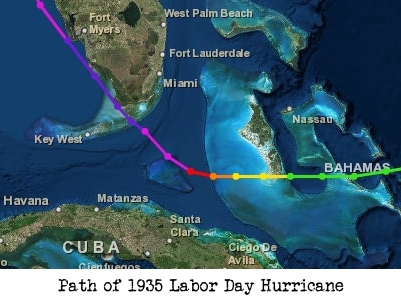

The breeding ground for most hurricanes is thousands of miles away, off the northern coast of Africa near Cape Verde. The 1935 Labor Day Hurricane was born as a tropical depression on August 31st, near Long Island in the southeastern Bahamas, a scant 375 miles from Islamorada in the center of the Florida Keys.

It reached hurricane Category 1 intensity (74 mph) the next day, September 1st, near the south end of Andros Island, approximately 175 miles from Islamorada.

There was nothing now between the rapidly intensifying storm and the Florida Keys besides warm summer ocean water that is rocket fuel for hurricanes.

Over the next 24 hours, the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane exploded into a Category 5 killer. The Weather Bureau’s 1:30 pm advisory on Labor Day, September 2nd placed the center of the hurricane 27 miles north of Isabela de Sagua, Villa Clara, Cuba (145 miles east of Havana) and projected it would pass through the Florida Straits on a westerly course.

The problem was that no one knew exactly where it was. As a safety precaution, hurricane warnings were broadcast from Key West north to Key Largo and planes dropped banners on areas without communication.

In the first recorded instance of a plane used to track a hurricane, Captain Leonard Povey, a Captain in the Aviation Corps of the Cuban Army and former circus performer, jumped into an open-cockpit Curtiss Hawk II biplane and soared into the sky to confirm it was heading toward Havana.

To Povey’s surprise, the hurricane wasn’t anywhere near the coordinates the Weather Bureau projected.

Then he spied it far off in the distance, on a northwest collision course with the Florida Keys.

Povey told the St. Louis Dispatch, “I was able to fly close to the disturbance. It appeared to be a cone-shaped body of clouds, inverted, rising to an altitude of 12,000 feet. The waves in the sea below broke against each other as if they were striking a sea wall.”

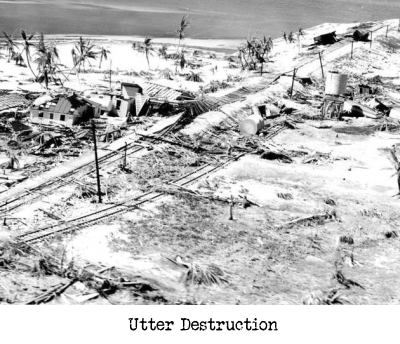

The length of the Florida Keys, from Key Largo to Key West, is 133 miles. In 1935, the population of the entire Keys, not counting Key West, was only 865 residents, but there were an unknown number of tourists in the area celebrating the Labor Day weekend.

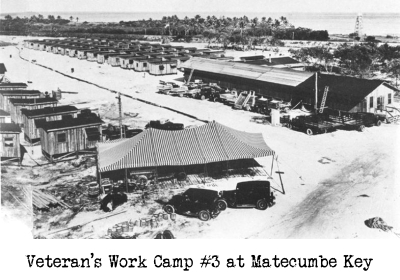

There were also three World War One veterans’ work camps on Windley Key and Matecumbe Key employing 695 men building the Overseas Highway connecting the mainland with Key West.

These unfortunate souls, employed in miserable conditions for $1 a day plus food and housing, would find themselves at Ground Zero when the hurricane came ashore. Many suffered from PTSD, known then as shell shock, with no other way to earn a living during the Great Depression. Fist fights were common and many drank away whatever money they earned to medicate themselves.

Time was now a quickly diminishing asset and there was not enough time to evacuate the Keys.

They also had no idea how strong the hurricane had become. It was a tiny hurricane, but very compact and incredibly powerful. The radius of its maximum winds was only about six miles, but if you were within those six miles at landfall your chance of survival was less than 50/50, and practically nil if you were caught out in the open.

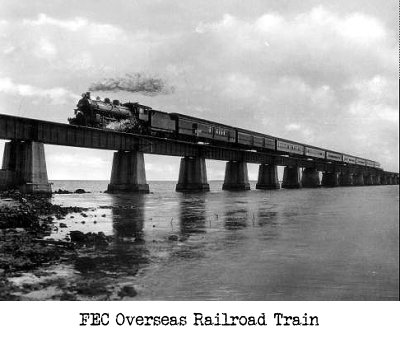

The veterans were housed in flimsy shacks that would disintegrate in a strong wind. The man overseeing the operation, Fred Ghent, the Florida Director of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, knew that the Keys were susceptible to hurricanes and had devised an evacuation plan. He would alert a special Florida East Coast Railway train in Miami to speed the 85 miles to Islamorada and retrieve the veterans.

After confirming that the hurricane was headed for the Keys, Ghent notified Miami at 1:59 pm to send the rescue train.

There was just one problem.

The Florida East Coast Railway had previously informed Ghent that if he wanted a train that could be sent immediately, he would have to pay to keep one ready on a separate track. For whatever reason, this was never done. A locomotive, tender and eleven cars would have to be assembled. This cost hours of precious time.

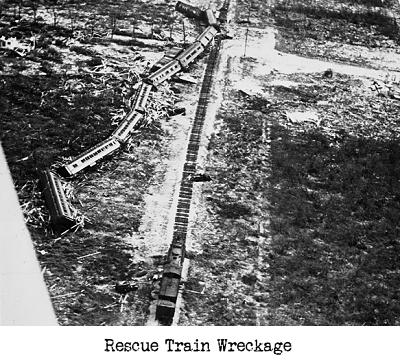

At 4:25 pm, the train finally departed Miami.

Engineer J.J. Haycraft cautiously eased his steam locomotive over tracks that were now being swept by waves as he nervously throttled his way down the Keys through rapidly deteriorating weather. He was in a race to get to Islamorada before the hurricane.

Luck seemed to be on his side until he was stopped by steel cable that had blown across the tracks just a few miles north of Islamorada. He had no choice but to get out and untangle the cable in gale force winds.

This took 80 minutes.

Blinded by wind and rain, the train finally reached its destination at 8:08 pm. Fifteen minutes later, the Labor Day hurricane slammed into Islamorada.

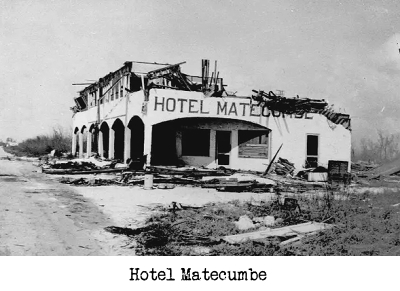

The official maximum wind speed for the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane is 185 mph. This was based on the barometric pressure of 892 mb. However, Hotel Matecumbe owner Ed Butters and his family were riding out the storm in his Plymouth automobile backed against a bus while he tightly held a barometer.

Butters and his family watched in jaw dropping horror as the barometer, illuminated by his flashlight, plummeted to 26.00 inches. It was too much to bear and terrified his family. He cracked open his window and tossed the gauge into the shrieking wind.

26.00 inches equals 880.46 mb.

880.46 mb equals winds in excess of 200 mph.

That’s the equivalent of an F4 tornado almost six miles wide.

The flimsy shacks housing the vets exploded into pieces. Coconuts shot through the air like cannonballs killing anyone in their path. The quartz beach sand sparked in the sky as the granules collided from the force of the wind.

The first to reach the rescue train were the camp administrators. They had no sooner begun to climb aboard when a 20-foot storm wave swept across the island knocking the train cars off the track. Only the 160-ton locomotive and tender remained standing. Amazingly, none of them died.

To escape almost certain death in the debris filled wind, some vets instinctively jumped into deeply dug pits as they had in the trenches during World War One. As the pits filled with water they drowned, their screams muffled by the roar of the wind.

The residents of Islamorada fared no better. Only eleven survived out of sixty-one members of the pioneer Russell clan, One young female mother in the family was found drowned 40 miles away near Cape Sable on the Florida mainland still clutching her dead baby.

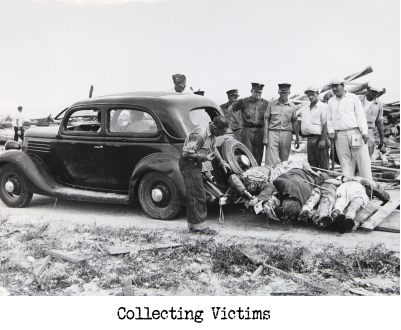

Bodies were discovered on Islamorada sandblasted to death with their flesh stripped down to their skull and bones.

Corpses quickly began to swell and split in the oppressive Florida summer heat. Fearing disease, authorities had no choice but to cremate them in stacked makeshift caskets overseen by religious officiants. 250 veterans were cremated on the banks of Snake Creek between Islamorada and Tavernier.

The official record of 485 fatalities is incomplete because some simply disappeared into the Atlantic Ocean or the Gulf of Mexico. In 1965, a developer dredged up an automobile with 1935 license plates. Inside the car were five skeletons.

Over 50% of those living in the Upper Keys perished on Labor Day, 1935. The population in the same area today is over 50,000.

The Labor Day Hurricane spelled the end of Henry Flagler’s Overseas Railroad from Key Largo to Key West. Completed in 1912, over 40 miles of track was destroyed by the hurricane and the Florida East Coast Railway was financially unable to repair it. The bridges and track were sold to the State of Florida who used it to complete the Overseas Highway.

If you drive down U.S. Highway 1 through Islamorada, you will see a memorial made of local coral limestone at mile marker 81.5. Dedicated in 1937, it features a beautiful frieze depicting palm trees and waves bending to the force of hurricane winds.

Inside the memorial are the cremated ashes of approximately 300 victims of the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane.

David J Castello